I’m really happy to finally share this. A selection of my photographs is featured on the cover and pages of PHOTOHOUSE Magazine, along with a full interview, released January 2026. It feels great to see this work come together in print, especially knowing how organically it all unfolded.

These images were made in Japan during a photography workshop led by Ted Forbes, founder of The Art of Photography and author of Visually Speaking.

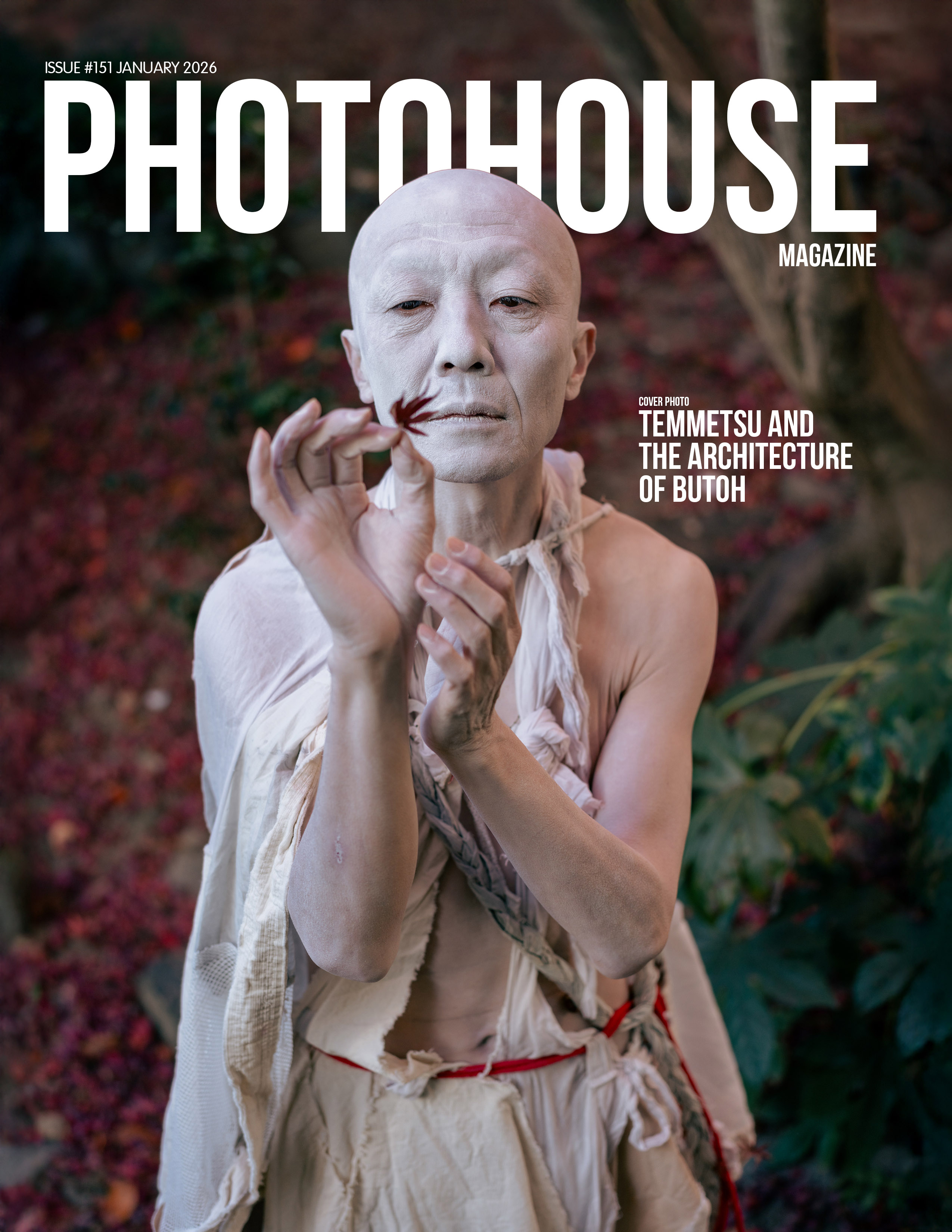

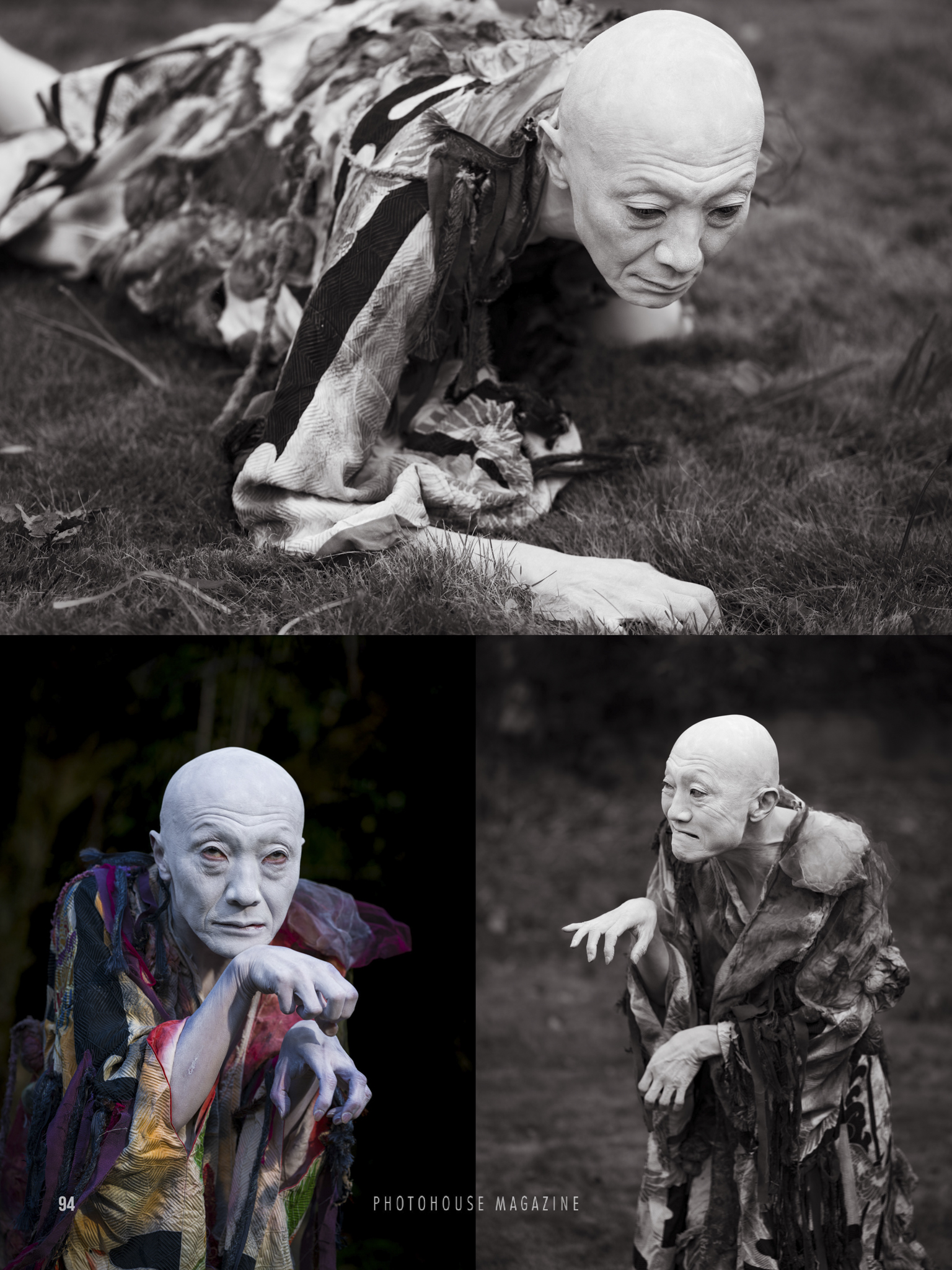

The workshop featured an intimate Butoh performance by Temmetsu, a Tokyo based dancer whose work explores subtle shifts between control and vulnerability.

Butoh encourages you to slow down and really look. Inside a traditional Japanese home and garden, the performance felt naturally connected to the space. Movement, stillness, and environment worked together in a quiet, thoughtful way.

As a photographer, I focused on observing. The goal was simply to respond to what was happening in front of me. Each image came from that place of attention, capturing small moments as they unfolded.

The interview in PHOTOHOUSE Magazine reflects on this process from three viewpoints. The performer. The educator. And the photographer. Together, they share the story behind the images.

ようやくこのお知らせを共有できて、とても嬉しいです。私の写真作品が、2026年1月発行の PHOTOHOUSE Magazine 第151号にて、表紙および誌面内で特集され、フルインタビューも掲載されています。自然な流れの中で生まれたこの作品が、印刷という形でひとつにまとまったことを、とても心地よく感じています。

これらの写真は、日本で行われた写真ワークショップの中で撮影されました。ワークショップは、The Art of Photography の創設者である Ted Forbes が主宰し、最後には東京を拠点に活動する舞踏家 Temmetsu による、親密な舞踏パフォーマンスが行われました。彼の表現は、コントロールと脆さのあいだにある繊細な変化を探求しています。

舞踏は、立ち止まり、じっくりと見ることを促します。日本の伝統的な家屋と庭園の中で行われたパフォーマンスは、その空間と自然に結びついているように感じられました。動きと静けさ、そして環境が、穏やかで思慮深い関係を築いていました。

写真家として私が意識していたのは、観察することです。目の前で起きていることに素直に反応する。それだけでした。ひとつひとつの写真は、そうした注意深さの中から生まれ、ささやかな瞬間が自然に形になっていきました。

PHOTOHOUSE Magazine に掲載されたインタビューでは、このプロセスを三つの視点から振り返っています。パフォーマー、教育者、そして写真家。それぞれの立場から、作品の背景と、この体験がどのように形作られたのかが語られています。

Credits

Butoh Dancer: Temmetsu

Workshop: Ted Forbes

Photography: Paul Tocatlian

The Interview

In Japan, a photography workshop can feel like a masterclass in attention. Not just attention to light, but attention to history, gesture, and the spaces that hold both.

During a recent Japan photography workshop led by Ted Forbes, educator and founder of The Art of Photography, participants moved through Kyoto’s temples and gardens, photographing environments shaped by restraint, ritual, and time.

The workshop culminated in an intimate experience that stayed with photographers long after the last shutter click: a live Butoh performance by Temmetsu, a Tokyo based dancer, staged inside a traditional Japanese home and garden.

Butoh is a Japanese performance art form known for its slow, deliberate movement, psychological intensity, and willingness to explore beauty and discomfort in the same breath. It often rejects spectacle in favor of presence, inviting the viewer to encounter transformation rather than entertainment.

In the quiet architecture of a home and the garden’s layered stillness, Temmetsu’s performance felt less like a scheduled event and more like a rare alignment of place, body, and meaning.

All photographs featured in this article were taken by Paul Tocatlian.

What follows is a curated conversation that interweaves three perspectives: the performer shaping time through movement, the educator designing an experience with cultural depth, and the photographer translating a live moment into still images.

Ted, what inspired you to include Temmetsu and Butoh dance as part of the photography workshop you organized in Japan?

I’ve always loved the works of Japanese photographer Eikoh Hosoe, who first gained attention in the 1960s. Hosoe’s seminal book Kamaitachi was the result of a collaboration with Tatsumi Hijikata, one of the founders of Butoh dance in the late 1950s.

Kamaitachi is essentially an illustration through photographs of a famous story about a super-natural being that haunted the countryside where Hosoe grew up. I was fascinated not only by the idea of photography as narrative in this project, but also in the collaborative nature of Butoh dance. I knew that an experience with a Butoh dancer would be a great photographic experience for the students. It also provides exposure to the post-war avant garde culture in Japan which is often overlooked in the west. Temmetsu has studied Butoh for years and is one of the great modern practitioners of this dance form.

Temmetsu, before a performance like this, how do you prepare your mind and body?

Rather than trying to focus, I consciously try to practice the Butoh principle of emptying myself.

Paul, how did this performance fit into the overall experience of the photography workshop in Japan?

Temmetsu’s performance felt like a natural continuation of the workshop. In Kyoto, we spent time photographing temples and gardens shaped by history and restraint. As someone drawn to photographing people and telling stories, experiencing his performance within that setting added a dimension I deeply value, where place, presence, and human narrative came together in a focused and meaningful way.

Ted, what responsibility do you feel when guiding photographers across cultural contexts?

My responsibility is making sure there is a respect for the culture being photographed. This should apply to every subject, but is especially important in a culture like Japan. I do a considerable amount of teaching online before we go and encourage the students to explore as much as they can. Being aware and respectful of a culture is the difference between immersion versus just making travel photography. I don’t want the students to come home with “postcard” images. I want them to experience as much of the culture first hand and come back with a portfolio of work that actually means something. Hopefully I’ve taken them someplace new artistically.

Temmetsu, how did dancing inside a traditional Japanese house and garden affect your movement?

There were many moments when the memories held within the land and the building seemed to enter into me. At those times, I think movements that I was not even aware of appeared naturally.

Paul, how did photographing Temmetsu change your approach compared to working on a fashion or editorial shoot?

Photographing a live performance is very different from working on a photoshoot. In performance, there is less opportunity to influence what unfolds. At the same time, there are similarities. Reading energy, movement, and emotional shifts is essential in both. This experience reminded me how much storytelling can come from attentive collaboration, even when that collaboration is silent.

Ted, how does teaching photography in Japan shape the way you think about learning and observation?

Japan gets me away from western concepts and ideas widely used in photography. Unlike the way art is taught in Europe or even America, Japan has strong roots in both Shinto and Buddhist philosophy which are centered around impermanence—the idea that beauty is given, peaks, fades and eventually dies so that the cycle can happen again. There is beauty, emotion and respect to every season. Much of the Japanese approach to art (and even life) is based around this concept.

The Japanese also have a deep respect for the mentor/student relationship. It’s really the ideal place for a workshop and exploring new ideas in photography. It’s a beautiful culture with a long history—the perfect place for a retreat to clear the mind creatively, explore new visual ideas and immerse oneself in a unique culture with a unique visual syntax.

Temmetsu, how is dancing in front of a camera different from dancing in front of a live audience?

When I dance in front of a live audience, I am aware of the flow of time itself, including its passage. In contrast, when I dance in front of a camera, my awareness often becomes heightened around “that moment”.

Paul, what is lost or gained when translating movement into stillness?

Translating movement into stillness becomes an exercise in storytelling. A single image demands precision about which moment carries the weight of the experience, while a sequence allows movement to unfold through rhythm and contrast. It revealed how much can be communicated through suggestion rather than explanation. By paying attention to gesture, tension, and continuity across frames, still images can convey motion, intention, and presence without showing everything at once.

Ted, when this experience is over, what do you hope participants carry with them into their own practice?

I intentionally set this workshop up to be an experience one wouldn’t have on their own and an experience that nobody else is offering. I provide access, but I want the student to gain a new cultural understanding and an artistic approach that is likely quite different from their own experiences. My goal is to push students into new ways of thinking and working with a new visual language. Japan is one of my favorite places in the world. I’ve found something there that continually draws me back and changes the way I think about photography. I want to share that with people who choose to come.

Temmetsu, when a performance remains as photographs, what does success mean to you?

That the person who sees the photograph is able to imagine something. I think it is fine whether that becomes their own story, an emotion, or a sensation.

© Paul Tocatlian. All Rights Reserved.